Your Cart is Empty

Forging a traditional Japanese katana wasn't an easy task. While many companies today sell cheap, mass-produced swords, bladesmiths during Japan's feudal period handcrafted katanas with an emphasis on detail and quality. This painstaking task often lasted for months, with bladesmithing investing their heart and soul into forging the iconic sword. Unless you're familiar with Japanese bladesmithing, though, you might be wondering why it took so long to make a katana.

Smelting the Steel

Before a bladesmith can even begin to forge the blade of a katana, he or she must first smelt the steel. Traditional Japanese katanas were made of the finest quality steel. Known as tamahagane steel, it consisted of higher concentration of carbon than standard steel. The added carbon content allowed for stronger swords that were less likely to fracture or break upon impact.

For three to seven days, the bladesmith would pour more than two dozen tons of river sand into a large furnace called a tatara. Temperatures inside the tatara would reach up to 2,500 degrees, allowing the carbon, iron and other compounds to evenly dissolve. When finished, the bladesmith would have about one or two tons of high-quality tamahagane steel with which to forge katanas.

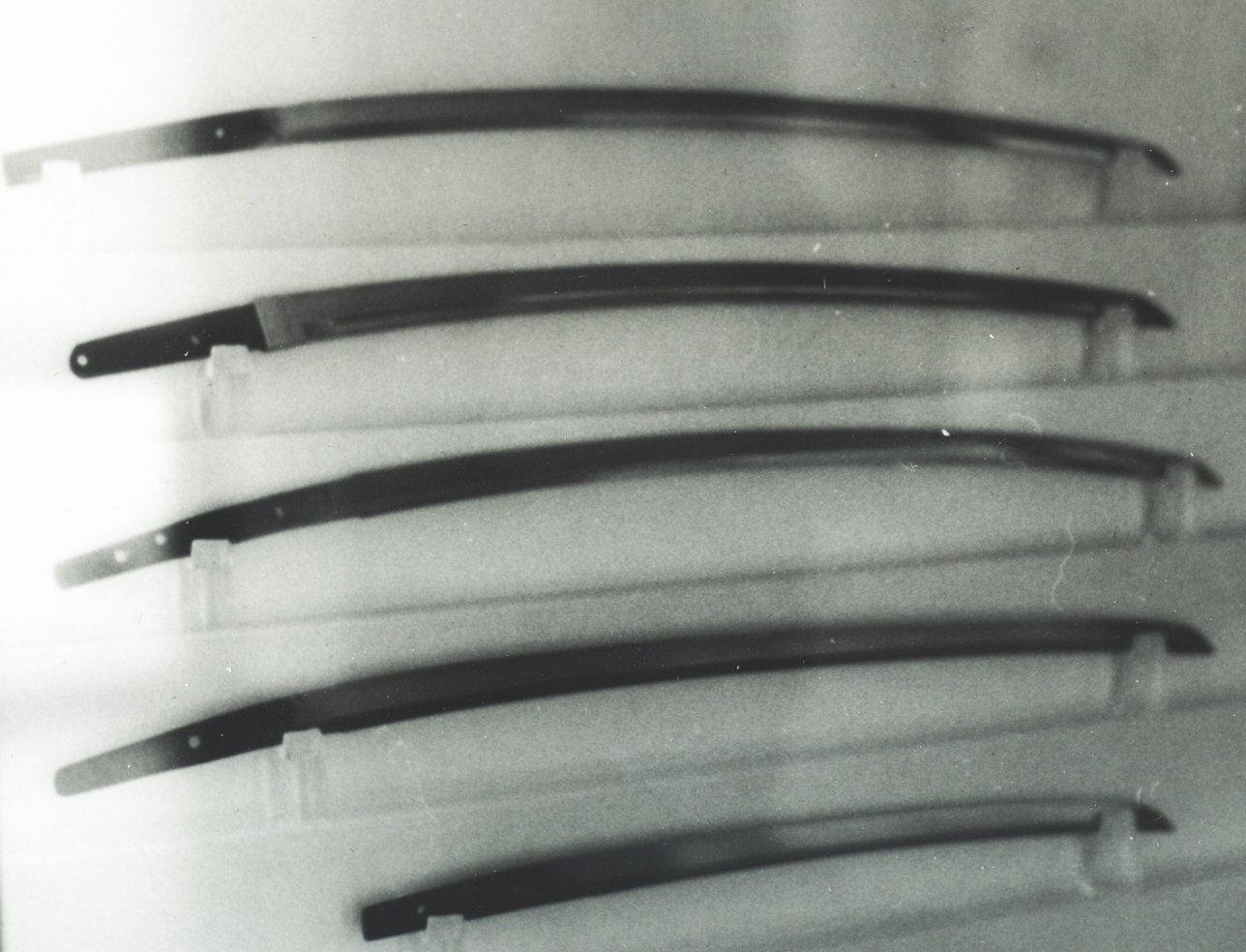

Folding the Steel

The next step to making a traditional Japanese katana is folding the blade. A bladesmith would hammer the tamahagane steel into the basic shape of a katana's blade. According to some reports, bladesmiths would perform this "folding" technique up to 16 times. The general belief is that each time the blade is folded, it becomes stronger. After about 20 folds, however, the strength benefits become less noticeable. This meant that most bladesmiths would stop after folding the blade about 16 times.

Differential Heat Treatment

Another time-consuming step to forging a traditional Japanese katana is performing differential heat treatment. Basically, this involves coating the blunt edge with clay, followed by submerging the blade in water. The layer of clay acts as an insulator, allowing the blunt edge (the spine) to cool more slowly the sharp edge of the blade. The end result is a blade with a very sharp edge and an elastic, bendable blunt edge.

Polishing the Blade

Before a traditional Japanese katana could be sold or otherwise given to a samurai warrior, it must be polished. Polishing a katana may sound simple enough, but it often took weeks of hard work. The bladesmith would pass the katana to a special worker whose sole job was to polish the blade. Normally, this worker would rub river stones over the blade to sharpen and refine its edge. When finished, the katana was ready for use.